For the last four years, since soon after the launch of the Jim Joseph Foundation’s Professional Development Initiative (PDI), every 12 months Rosov Consulting has interviewed a sample of participants from each of the 10 grantee programs. These interviews have explored educators’ motivations for participating in the programs, what they experienced during the time they took part, what they gained from these experiences, and, finally, what program alumni perceive to have been the impact of these experiences on the trajectory of their professional careers.

Although the Professional Learning Community made up of participants in the PDI formally disbanded more than a year ago, the work of the evaluation team has continued. As planned, toward the end of 2021, the evaluation team returned for one last round of clinical interviews with alumni of the program, and over the last few months the team has continued to field the Shared Outcomes Survey to program participants, typically between two and six months after their programs concluded.

These deliverables show that the programs fulfilled their core goals:

- Shared Outcomes Survey data indicate that, overall, the programs helped participants become much more knowledge about and more accomplished in performing the professional tasks for which they are responsible, what we called “ways of thinking and doing.”

- Clinical interview data indicate that these professional outcomes have been quite durable, although with the passage of time interviewees found it increasingly difficult to draw causal links between what they know and can do today and what they gained from their programs.

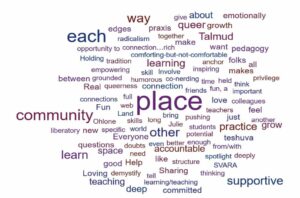

- Survey data also show that, taken together, the programs have socialized participants into professional communities that the participants very much value. Again, interview data depict how important these communities have been, especially since the start of the pandemic, and how, in the words of one interviewee, “relationships have become partnerships.”

- Finally, survey data reveal the degree to which those program participants who started out with less intensive Jewish backgrounds have had an opportunity to grow and feel more confident as Jewish educators.

The evaluation work Rosov Consulting conducted has helped identify the features of high-quality professional development, both in conceptual terms and by means of thick accounts of how such features are formed and experienced (through five case studies).

The Jim Joseph Foundation Professional Development Initiative – Taking Stock and Offering Thanks: Year 4 Learnings, Rosov Consulting, May 2022