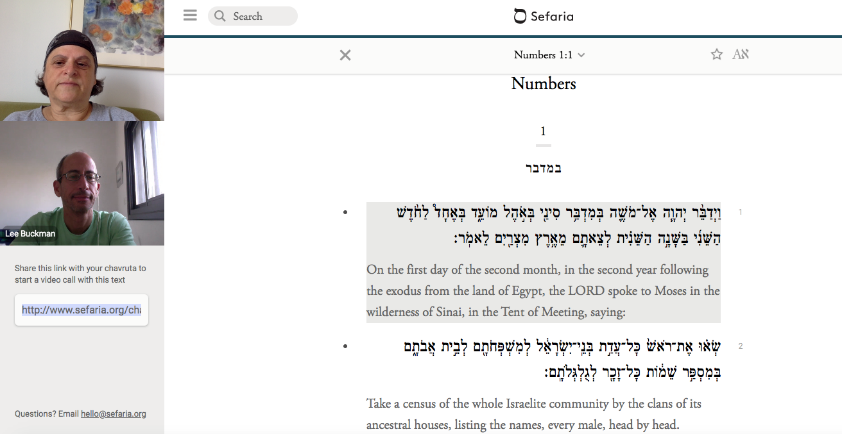

In recent years, my chevrutah (study partner) and I have enjoyed studying musar – a body of Jewish thought focused on human character development and the many middot / character traits an individual can cultivate throughout their lifetime. Menachem Mendel Lefin of Satanov dedicates an entire chapter of his book Cheshbon HaNefesh (1808) to the middah of charitzut / decisiveness. He states, “All your acts should be preceded by deliberation; when you have reached a decision, act without hesitation.” This important advice is meant to empower the learner to avoid the pitfalls of decision paralysis, inviting them to develop plans and stick with them.

But like many teachings in musar (and in life) there are equally compelling lessons that stand in opposition to Lefin’s teachings. One Talmudic source, in Taainit 20b, explains that a person should be rach k’kaneh, “soft like a reed, not be stiff like a cedar.” This text teaches that we need to bend our plans when new information challenges our assumptions.

So which is it? Be decisive or be flexible? Navigating paradoxes like this are at the core of musar practice—acknowledging contradictory truths and becoming adept at knowing when to rely on one or the other. Contemporary leadership theorists also explore this same notion using the language of “polarity thinking.” Doctors Valerie Erhlich and Brendan Newlon summarized this in their May 2019 report for the Jim Joseph Foundation stating:

Polarity thinking is about navigating a set of two qualities that are both beneficial, yet they exist in tension with one another… Managing that tension effectively can be challenging, because the most appropriate response to a specific circumstance might be an expression that favors one or another of the pair – maintaining a simple balance between the two might be impossible or undesirable.

At the Jim Joseph Foundation, we navigate these dynamics as we continuously shape, implement, and reflect on the Foundation’s grantmaking strategy. A persistent challenge in grantmaking work—especially these past two years—is to determine how and when should we stay firm and how and when should we be flexible amid constantly changing circumstances.

This piece explores our attempts to shape and re-shape our grantmaking plans in recent years—pre-pandemic, during the pandemic, and this current period of emerging (we hope) into a post-pandemic world. In examining our journey through the lens of this polarity—being firm and being flexible—we hope to offer insights on this ongoing internal decision-making process. We welcome a dialogue about whether this story sounds familiar, or not, as you reflect on how the organization you are connected to made its own decisions during this tumultuous time.

Chapter 1: Pre-pandemic

In 2017 the Jim Joseph Foundation entered a two-year process to develop a new strategic framework for its grantmaking. We began with fundamental questions:

- What had we learned in the years since the Foundation began?

- How has Jewish education in the United States (which is the core focus of our funding) evolved?

- What could we uniquely contribute to this field during the next phase of our work?

These questions guided our dialogue with external partners, professional staff, and our board. Eventually, we arrived at a new theory of change that included core assumptions, guiding principles, long-term outcomes, and a set of three strategic priorities to invest in (1) powerful Jewish learning experiences, (2) exceptional Jewish leaders and educators, and (3) R&D for the future of Jewish learning. To accompany this Theory of Change, we also developed logic models, grant categories, and a detailed five year implementation plan. All of this was based on careful thinking, assumptions about where the sector was headed, and how we believed we could be a positive influence.

By January of 2020, after reviewing these plans with each of our key stakeholders, we were excited to implement our new strategies and to determine how to measure our progress. Yet, as the old Yiddish adage goes, “mann tracht, un Gott lacht”—we humans plan, and God laughs.

Chapter 2: During the Pandemic

When the world turned upside-down in March of 2020, like everyone, we recognized the need to be rach k’kaneh – soft like a reed – in the face of uncertainty:

- We reluctantly set aside our multi-year plan and shifted our focus to short-term planning in 1-3 month increments.

- Our first priority was to support the work of our core grantee partners to weather the pandemic and economic crisis.

- We also joined with a cohort of other funders to build the Jewish Community Response and Impact Fund (JCRIF), a collaboration designed to provide rapid responses to emerging needs.

Another important focus was taking a more proactive stance around learning and sharing about the pandemic’s effects on Jewish education.

- We built our expertise in emerging areas of need: strategic restructuring, unemployment, stress and anxiety, increased interest in online learning/digital engagement, growing interest in home-based and do-it-yourself Judaism, and rising communal desire to address systemic racism within Jewish education.

- We funded research to better understand how young Jews, educators, and funders were responding to the crisis; what solutions were and weren’t working; and what creative adaptations might be worth sustaining long-term.

- We increased efforts to share these learnings through published reports, presentations, and small group conversations.

As we dedicated time and resources to these new priorities, we made difficult choices about scaling back in other areas. We postponed some of the new grantmaking programs from our pre-pandemic implementation plans, recognizing they would need to wait until we, and our grantee partners, had enough bandwidth to design and implement them. We also temporarily moved from multi-year to one-year grants to retain greater flexibility for the Foundation and our grantee partners. This was particularly difficult since we knew that it would introduce additional uncertainty for grantee partners who had previously planned for a longer-term commitment from the Foundation.

Working in this more flexible way was unfamiliar territory for the Jim Joseph Foundation team (and counter-cultural for many who work in institutional philanthropy) but we recognized the need and opportunity to practice being rach k’kaneh, soft like a reed.

Chapter 3: Emerging (we hope) into a post-pandemic world

In recent months, as the world is moving cautiously back to in-person gatherings, our team has begun to methodically revisit the long-term plans we designed prior to the pandemic. While the world has changed, we are encouraged that some of our previous assumptions about the evolution of Jewish education hold true, in some cases even more so than before.

Because our core strategies were built around fundamentals like building organizational capacity and investing in talent, the basic framework of our plans still serves us well. Similarly, the opportunity for increased investment in R&D remains unchanged and, within a context of such rapid change and possibilities, is perhaps more pronounced than ever.

At the same time, as we get into the details of the implementation plans we previously designed, we see the need to update them with a new grantmaking mindset and a new understanding of what is important to and needed by our beneficiaries. That in mind, we are:

- Updating what was previously planned. As we begin to launch new programs mapped out in 2019, we are redesigning them for increased flexibility and new features such as integrated online and in-person learning, a greater emphasis on wellness, and centering more diverse voices and partners.

- Returning to our best practices. Starting in April 2021, we gratefully returned to multi-year grantmaking, working with our grantee partners to make sure that their plans remain both relevant and flexible in the face of new realities and continued uncertainty. In some cases, we are continuing with shorter-term investments to support our grantee partners to spend additional time rewriting their multi-year plans.

- Maintaining new collaborations. Working with the coalitions we joined to engage in emergency grantmaking, we are exploring ways to sustain new collaborative investing practices such as joint proposal invitations and coordinated, rapid response grantmaking.

- Doubling down on what we know is needed. The pandemic has also sharpened our understanding of the importance of R&D as a strategy to address shifting societal and marketplace trends to guard against organizational stagnation and pursue new opportunities.

As much as our Foundation team always valued and found comfort in a highly structured framework for our work, we now have a deep appreciation of the need to balance our dedication to well-laid plans with a readiness to remain nimble as new opportunities and realities emerge.

Contemporary musar teachers advise learners to write their own “spiritual curriculum” – choosing middot to focus on based on their own unique circumstances and needs. Embedded in the whole musar framework is an ongoing process of hitlamdut – learning and reflection. This is one of our Foundation staff values, an acknowledgment that we will always have room to learn and improve. The goal is not perfection, the goal is to stay on the path.

Looking back with 20-20 hindsight we can always see our own imperfections – the moments over the years when the Foundation was unnecessarily inflexible, and other places where the opposite was true. As a result of the challenges of the past 18 months, we move forward as a team, better understanding when to embrace charitzut and when to be rach k’kaneh. This is wisdom we hope to apply in the future.

Josh Miller is Chief Program Officer of the Jim Joseph Foundation.