On a recent June night, 25 people, primarily young children, sat on their couches and watched as a puppeteer explained how he creates his puppets and how they could build their own with materials they have one hand. In another “room,” about a dozen people watched as an artist explained how he uses paints to create depth and design.

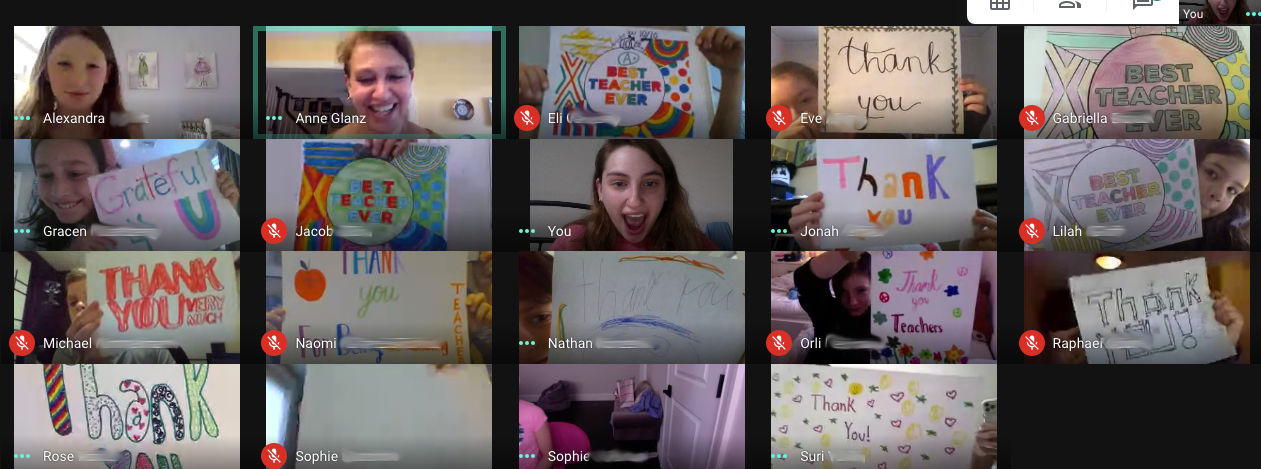

Welcome to the annual end-of-year art celebration at Charles E. Smith Jewish Day School in Rockville, Md. Traditionally held in person, this year’s event—like events at schools around the country—took place online with the “rooms” separate live video streams that families could tune into.

Across the country, Jewish day schools were quick to pivot from a traditional in-class setting to online classrooms, and as the academic year winds down, they are taking stock of where they stand, what they have accomplished and how to move ahead in a COVID-19 world.

“Jewish day schools have worked incredibly hard, and as a result, we have been world leaders in providing a virtual education in this period,” said Paul Bernstein, CEO of Prizmah: Center for Jewish Day Schools.

A New York Times article on May 9 highlighted the success of remote learning at the Chicago Jewish Day School, which provided more than four hours of live, online instruction daily after the coronavirus caused brick-and-mortar schools to close their doors this spring, in comparison to many public schools that provide only limited live, online programming. Other Jewish day schools, similarly, provide multiple hours of online instruction each day.

“As a private school, we had leeway and flexibility to get creative about the way we were teaching and make sure we reaching the whole child’s emotional and social well-being, even if it’s through a screen,” said Ilyssa Greene Frey, director of admissions at The Rashi School in Dedham, Mass., a Jewish elementary school outside Boston.

Part of the that early success came as a result of the pandemic hitting the Jewish community in New Rochelle, N.Y., particularly hard in early March. The Salantar Akiba Riverdale Academy (SAR) was the first Jewish school—and the first school in the nation—to shut down on March 3. It reopened virtually two days later, and within days, was sharing its findings on virtual education in a webinar with other Jewish day schools around the country, facilitated by Prizmah.

Right away, teacher training went into effect on how to utilize a virtual-learning platform with communication to parents about the next steps. Administrators also ensured that all students had access to computers or iPads for class and arranging for electronic devices for those students who did not; in a number of cases, families may have had only one device and the parents were using it, or there were not enough for each child in a family to be online at one time.

That level of detail, along with online instruction that seemed to run circles around what the public schools managed to offer these past few months, has attracted interest from Jewish families that previously had not considered a Jewish day school for their child.

Officials at The Rashi School, which enrolls 250 students in grades kindergarten through eight, began seeing interest from prospective parents relatively soon after its classes went to an online platform on March 18.

“Families are seeing that Rashi is able to provide an education experience for their children that the public schools just cannot, and that is driving some the inquiries we are getting,” said Frey, noting that officially, admission for the 2020-21 school year closed just before the pandemic hit.

She notes that interest from new families has been particularly strong for enrollment in its middle school, where tuition can run upwards of $40,000. (Tuition begins at $29,900 for kindergarten and goes up from there.)

Among the new families joining the school will be the Shilman family, with eldest son Nathaniel starting kindergarten this fall.

“In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, we remain uncertain what the next school will be like; however, our decision is more certain than ever,” said Nathaniel’s mother, Stella Shilman. “Rashi has been great at keeping new students up to date with plans during quarantine and continuous efforts in online learning. From my conversations with other families, Rashi was able to quickly transform to virtual classes and continue to advance academic studies while maintaining connections within their community, beyond walls of the school.”

Those connections, said Shilman, included a virtual “play date” where Nathaniel got to meet some of his new classmates.

The Jewish Community Day School of Greater New Orleans has also seen increasing interest in its program.

“We’ve had a few families that are looking at us more seriously and a few that have already applied not just because of what we’ve done online, but because we are a smaller school and they feel we can take appropriate precautions for in-person learning,” said Brad Philipson, the Oscar J. Tomas head of school chair. The school is also working with a regional hospital system that has developed a safe-return system for when classes reopen in August.

According to Rabbi Mitch Malkus, head of school at Charles E. Smith Jewish Day School, for those families who could afford to send their children to day schools but “weren’t committed to the value proposition of spending time in a Jewish day school, this has changed the equation for them. They may have felt in the past that the public school was good enough, and now they are seeing it is not good enough.”

At Charles E. Smith, parents who have been impacted by a job loss or furlough because of the pandemic will be eligible for tuition from a special emergency fund so as not to strain the general tuition-assistance fund. “We look at COVID-19 as something that will have a one- or two-year impact on tuition-assistance requests,” said Malkus, “but we wouldn’t be able to sustain this additional level of support in the long run.”

Malkus added that local donors have stepped up, but he’s hoping to secure even more gifts.

“When we were thinking about our emergency fund, we looked back to see what was needed in the great recession of 2008-09, and historically, how many people left the school,” said Malkus. “We are trying to address economic crisis from COVID-19 as best we can. My hope would be that the Jewish day-school field and schools individually are working to address that this time around in ways we didn’t during the great recession.”

“At the end of the day, unfortunately, everyone has limited resources, and there is only so much fundraising that can be done, and the impact of the pandemic is pretty significant,” he added.

Malkus said that prospective families were able to join in the end-of-year, online art program, and that more than a dozen families participated in a recent virtual open house. Like at Rashi, much of the interest for new enrollment is in the upper grades—both the middle and high schools. Currently, there are 920 students over two campuses in the pre-k through 12th-grade school.

Financial, enrollment and donor-support challenges

While an uptick in enrollment is good news, especially as the trend was moving in the opposite direction in recent years for non-Orthodox day schools, some 34,000 Jews attended a non-Orthodox day school in 2013, according to a report from the Avi Chai Foundation, down from some 39,500 in 2003. It comes as schools face new financial challenges as they examine how to reopen schools in a few short months.

Finances are always a concern for Jewish day schools, but even more so now as parents have been furloughed or laid off completely, economic downturns have impacted donors’ wealth portfolios, and the costs of doing business will rise to meet the myriad of health and safety guidelines and regulations needed to reopen schools as early as August.

A survey of 110 heads of Jewish day schools conducted by Prizmah recently found that 90 percent of them were expecting at least a 10 percent increase in tuition-aid requests for the upcoming school year, while two-thirds of schools said they anticipate tightening their budgets.

There is precedent for their concern.

During the economic crash of 2008-09, Jewish day schools across the country were hit hard. Parents who were facing financial challenges pulled their children from Jewish day schools because they could no longer afford them. A number of school even shut their doors for good, unable to keep up with the declining enrollment and fiscal shortfalls.

The 2020 landscape, say experts, is quite different.

“We’re not hearing there is a big re-enrollment crisis, but we are hearing a lot of need for tuition from families that are struggling, particularly in families where one of both parents may have lost jobs or been furloughed,” said Bernstein.

To help ease that burden, Prizmah recently announced that it will be launching two new tuition-assistance funds for families impacted by the pandemic. One will be general tuition-aid fund, and the other is specifically for those parents who work in the Jewish communal sphere.

Both grants are being supported by the Jewish Community Response and Impact Fund, an $80 million fund that was established to help a variety of Jewish organizations and institutions weather the fiscal impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. JCRIF is being backed by the Aviv Foundation; the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation; the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Foundation; the Jim Joseph Foundation; Maimonides Fund; the Paul E. Singer Foundation; and the Wilf Family Foundation.

Schools are also trying to encourage local donors to step up.

In New Orleans, for instance, school officials had hoped to raise $15,000 during the Give NOLA Day, a citywide, annual charity event. When the pandemic began and the event was postponed until June, school officials were concerned people wouldn’t be able to give so they lowered their initial benchmark to $10,000.

They wound up raising $27,000 through the campaign. (People were able to give as early as May, even though the actual “day” was pushed back.)

“The community really stepped up,” said Philipson. “We don’t have the kind of money in New Orleans that bigger cities do, but we have a lot of philanthropists who are very dedicated to the Jewish community.”

At Charles E. Smith, parents who have been impacted by a job loss or furlough because of the pandemic will be eligible for tuition from a special emergency fund so as not to strain the general tuition-assistance fund. “We look at it as something that will have a one- or two-year impact,” said Malkus, “but we wouldn’t be able to sustain it in the long run.”

Malkus added that local donors have stepped, but he’s hoping to secure even more gifts.

Even with assistance for parents, fiscal challenges hover above potential openings this fall.

Laurence Kutler, head of school at the Tucson Hebrew Academy in Arizona, estimates that reopening his school in early August with all the necessary health guidelines in place will cost a minimum of $40,000, including hiring an additional employee to help with sanitizing the school between classes.

That dollar amount, however, does not include the purchase earlier this year of Chromebooks for students who didn’t have access to one at home. Funds for those computers came from a private donor. The kindergarten through eighth-grade school is attended by 122 students.

“We have 38 pages of protocols from the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] and the governor’s office, including hygiene-sanitizing equipment, social distancing in classrooms and teacher-student ratios,” said Kutler, adding that they are saving some funds by bundling their supplies with the local Jewish community center and Jewish federation to keep costs on masks, gloves and hand sanitizer down.

Said Malkus, “When we were thinking about our emergency fund, we looked back to see what was needed in the great recession of 2008-09, and historically, how many people left the school. We are trying to address that as best we can. My hope would be that the Jewish day-school field and schools individually are working to address that this time around in ways we didn’t the first time.

“At the end of the day, unfortunately, everyone has limited resources, and there is only so much fundraising that can be done and the impact is pretty significant,” added Malkus.

Incorporating scenarios for social distancing, eating, recess

With so much uncertainty regarding COVID-19—and concerns of a second or third wave of the coronavirus expected come winter—nearly every school JNS spoke with is preparing various scenarios for running the 2020-21 academic year. Saying anything is certain remains … uncertain.

“We have a variety of scenarios planned,” said Wendy Leberman, director of admission and marketing at the Jewish Day School in Bellevue, Wash., the city now known for the overwhelming large number of elderly who died in nursing homes. “We have large campus and small class sizes, so if we are limited to 10 kids a classroom, we’ve looked at how we can do that. We’ve also planned how we can can go back to campus at a 100 percent [normal], how we can do remote learning in the fall or a hybrid of the two.”

Leberman said one idea is how to have teachers educate multiple classes without risking exposure from different sets of students. One solution: having an educator remain in one room to teach classes live to be broadcasted virtually to students in other classrooms.

Some schools, particularly those with large campuses or in suburban areas, are talking about taking lessons outside, at least on good weather days, with virtual classes during cold or inclement weather. Other institutions are anticipating having a group of students in class some days, with others working virtually, and then switching either weekly or every other day. (Israel began a similar policy upon first opening its schools.) Most school concede that class sizes will be kept to a minimum per state guidelines to allow ample distancing between children.

Lunch and recess are also being reimagined. Many schools said they will focus on eating in classrooms. Some added that children and teachers will be responsible for wiping down desktops before and afterwards. Because class sizes will be significant smaller—the current best estimate is 10 to 12 students per classroom—with one teacher and perhaps an aide, adults will be better able to watch that students don’t share meals or snacks.

Recess will likely be staggered so that classes aren’t mixing on the playground or ball fields. Educators will also be looking at how camps running this summer handle their sports and free time for ideas for games and athletic activities that can be done with little contact.

Also, the school day may be shortened in some areas to allow for staggered shifts and more cleaning times, which would affect recess.

Whatever it looks like, 2020 will be like 2008—a “pivot point” for Jewish education, suggested Bernstein. “The question is: How do we pivot to have good things happen? And if that means there will be some consolidation among schools in a particular area, that’s a real possibility.

“We aren’t just talking about schools closing, but of schools coming together and making something that is stronger than their individual parts,” he continued. “ … There are even opportunities between schools to share the virtual platform, which can be cost-saving. There are lots of creative ideas ahead.”

Source: “Amid the pandemic, Jewish day schools survive (and even thrive),” Faygie Holt, Jewish News Syndicate, June 19, 2020