This piece from Jakir Manela, CEO of Hazon & Pearlstone, with contributions from Rabbi Zelig Golden, Executive Director of Wilderness Torah, and Adam Weisberg, Executive Director of Urban Adamah, shares lessons learned from JOFEE leadership during the recently completed three-year period of the Jim Joseph Foundation’s general operating grant to Hazon, as well as lessons learned over the last ten years of the Foundation’s support to the field.

At Hazon and Pearlstone, we believe in the centrality of adam and adamah, people and planet. Our mission is to cultivate vibrant Jewish life in deep connection with the earth, catalyzing culture change and systemic change through immersive retreats, Jewish environmental education, and climate action.

The parallel issues of declining Jewish affiliation and the global climate crisis are not unrelated. Climate grief and anxiety are now diagnosable mental health crises that impact young people across the Jewish world. Young Jews tend to care more about climate and sustainability than older generations, and they are also less likely than older generations to affiliate with Jewish institutions. For many, what keeps them up at night is not Jewish survival, but human survival.

It was almost 10 years ago that the term JOFEE (Jewish Outdoor, Food, Farming, and Environmental Education) was coined by a group of funders. Collectively, the Jim Joseph Foundation, Leichtag Foundation, The Morningstar Foundation, Rose Community Foundation, Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Philanthropies, and UJA – Federation of New York invested in the Seeds of Opportunity JOFEE report. They discovered—through robust third-party research—a movement that was making a significant impact across the Jewish world. Since then, the Jim Joseph Foundation investments focused on supporting the four largest JOFEE organizations — Hazon, Pearlstone Center, Urban Adamah, and Wilderness Torah—and launching the JOFEE Fellowship in order to both professionalize and expand career opportunities across the field.

Over four years, the JOFEE Fellowship trained more than 60 young adults as educators, placing them at Jewish organizations including JCCs, federations, summer camps, and more. For fellows, the chance to create change by bridging their environmental concerns with their Jewish identities was a key motivation for joining the program:

“I was sick of being Jewish for the sake of being Jewish,” one wrote. “I’m here because I think being Jewish really matters in the world.”

In 2019, the Jim Joseph Foundation further invested in these organizations for an additional three years. Over these years, we learned lessons and gathered insights as our field grew and evolved.

The Growth and Diversification of the Community of People Engaging in JOFEE

As the pandemic unfolded, Jewish outdoor education quickly became a go-to for communities. Programs have grown both in the number and type of participants they’re engaging—including wider age ranges, geographies, and affiliation levels. Both the accelerated adoption of virtual programming, and the desire of people to re-engage in in-person programming as the world reopens, means that we have so far maintained new program growth, and expect to continue to do so into the future. As a result, JOFEE now reaches a broader audience.

Reflecting this growth, Wilderness Torah and Camp Newman will create the Center for Earth Based Judaism, a learning center for all segments of the community, and focus on earth care and climate resiliency. As Wilderness Torah builds regionally, it also is scaling nationally with programs such as Neshama (Soul) Quest and Jewish backpacking trips. And while its festivals are transformational, the organization has identified a need for smaller bite-sized programs across urban areas to increase participation: after going to two to three small programs, people begin to attend larger events.

As for Hazon and Pearlstone, in 2023 the two organizations are merging into the largest Jewish environmental non-profit outside of Israel. Our two retreat centers (Isabella Freedman in CT, and Pearlstone Center in MD) were hit hard by the pandemic, but we also saw tremendous growth in our programmatic impact. In the words of one parent whose child was in a weekly program: “While the children are busy feeling free and happy and honing their favorite skills, our parental spirits are soaring because we know [they’re being guided] toward full aliveness, sensitivity, and responsibility to the world around them.”

Nature is a Profound Driver of Reconnection to Jewish Life

In this age of digital overload and hesitancy surrounding indoor gatherings, a nature-connected, outdoor Judaism speaks directly to what we need in mind and body, heart and soul. Despite myriad online opportunities, people continue to seek the authentic sense of purpose and connection that can be found through engaging with the more-than-human world.

A Wilderness Torah participant commented:

“I experienced a profound healing in the part of my soul that has been searching for a tribe and embodied Jewish community. My Jewish heart and connection to my ancestors has opened. I have found my home as a Jew.”

We have also witnessed JOFEE’s ability to connect youth to wider Jewish communal life. If we provide meaningful experiences, youth can and do stay engaged. We need to ask ourselves: How do we authentically connect with who we are at our rooted core, to the obligations and responsibilities of what it means to be a human on planet earth?

Jewish Youth and Young Adults are Seeking Opportunities to Lead on Environmental Issues – Whether in the Jewish Community or Not

Perhaps one of the biggest lessons learned over the past years is the growing demand from and for Jewish youth to be empowered as their own leaders and educators in environmental work and action. Hazon’s Jewish Youth Climate Movement (JYCM) was launched in 2020 and in just over two years blossomed into over 44 Kvutzot (chapters) nationwide, each with 10-30 members — a strong indicator of the need for these kinds of outlets. Efforts run by the teens themselves reach about 10,000 more people each year. These chapters are not just powerful Jewish engagement opportunities; they are also a safe space for young people who may not feel accepted with their full Jewish identities amid some elements of anti-Zionism and antisemitism in the secular climate justice movement.

One teen commented:

“Previous to my engagement in JYCM, I was in a youth-led movement that…taught me a lot about the climate crisis and how to organize…However, at times it felt as if I had to choose between my Jewish identity and organizing as the movement had been involved in some anti-Semitic activity and my specific chapter was unwilling to publicly condemn it.”

We see college campuses as an area of critical growth on the horizon, as Hillels have been among the most active participants in Hazon’s climate action and sustainability programs to date. As young adults seek ways to get involved, many look for hands-on experiences. For example, Urban Adamah runs an alternative spring break experience combining sustainable agriculture and Jewish community building.

A theme among these programs is participants’ desire to make a difference in the world overall, not just within the Jewish world. As such, JOFEE programs are increasingly welcoming young adults’ non-Jewish friends and family members. This helps to foster participation and widens the tents of involvement and belonging for those wishing to become active in community building and organizing.

Jewish Communal Interest and Action on Sustainability is Growing, Presenting New Opportunities for Collaboration within the Wider Jewish World

For many of the JOFEE field’s participants, the climate crisis is an overarching emotional and spiritual theme, present in their daily lives. And Jewish tradition has a direct, powerful, and unique response to these concerns. For over 20 years, we have unpacked Jewish ecological wisdom to connect people with their own inspiration, and an empowered community of peers to build with. Moving forward, we aim to interweave Hazon and Pearlstone’s programs in order to facilitate greater networking, collaboration, and leadership among participants.

Hazon’s growing national portfolio of virtual and in-person programs provide options for pop-up collaborations. At the same time, Jewish youth are increasingly seeking leadership opportunities within JOFEE — a useful avenue for them to create meaningful experiences while also building a network of peers. We approach the end of 2022 with a new and diverse set of programs and participants, including a network of hundreds of Jewish teen activists across the country via JYCM; a newly launched Jewish Climate Leadership Coalition with over 120 Jewish organizations, three major national community hubs engaging tens of thousands of people a year in Baltimore, New York/Connecticut, and Detroit; and a programmatic framework that enables seamless online and in-person fusions. With Wilderness Torah and Urban Adamah also scaling programs to a national level, as well as increasing their regional impact, it is increasingly possible for young Jewish individuals to find their place in a Jewish community that shares their environmental values.

As we expand our ability to engage youth and young adults on the issues that matter most to them, we also renew Jewish communal life by empowering them to build their own communities of meaning, purpose, and connection.

Jakir Manela is CEO of Hazon & Pearlstone, which cultivates a vibrant Jewish life in deep connection with the earth. Rabbi Zelig Golden is Executive Director of Wilderness Torah, which promotes healing, belonging, and resilience by awakening and celebrating earth-based Jewish traditions. Adam Weisberg is Executive Director of Urban Adamah, an educational farm and community center in Berkeley, California that integrates the practices of Jewish tradition, mindfulness, sustainable agriculture, and social action.

The place where Jacob slept only became sacred because he stretched his imagination of who the Jewish people could become and how this place could foster purposeful gathering. This offers a more dynamic model of sacred sp

The place where Jacob slept only became sacred because he stretched his imagination of who the Jewish people could become and how this place could foster purposeful gathering. This offers a more dynamic model of sacred sp be shared with our new synagogue landlords, allowing us to create a home for Jewish prayer, learning, and community characterized by both stability

be shared with our new synagogue landlords, allowing us to create a home for Jewish prayer, learning, and community characterized by both stability

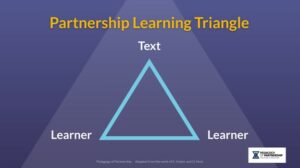

PoP at school, reflecting on the very questions we asked parents to consider about the nature of havruta learning. The students offered practical advice for how to make the most of one’s learning. Parents were enchanted and took to heart their children’s sound advice:

PoP at school, reflecting on the very questions we asked parents to consider about the nature of havruta learning. The students offered practical advice for how to make the most of one’s learning. Parents were enchanted and took to heart their children’s sound advice: