“What would remain if Foundation funding disappeared?” This was a common question that former Jim Joseph Foundation Executive Director Chip Edelsberg posed to challenge the professional team during the early launch phases of Foundation-supported teen education initiatives. But really, the question itself reflects a guiding principle of the Foundation since its inception; that is, to support organizations and initiatives in ways that are sustainable so that Jewish learning endeavors live on—and continue to benefit young people—even after a grant period concludes.

This principle, essentially a goal for each grant, has informed grantmaking decisions and the lengths and structures of Foundation grants. We have learned lessons over the years about strategies and approaches to make this goal more likely to be achieved, including awarding matching grants to encourage new funding sources, supporting grantee-partners’ strategic planning processes, open and frequent conversations with grantee-partners, setting expectations with grantee-partners, and providing grantee-partners with enough time to position themselves for success if and when Foundation funding ceased. We have also gained a deep understanding about the power of a capacity building grant to help a grantee-partner grow in a sustainable way. Through trials and errors—and some fail forwards—we have learned about both the benefits of growing and the potential risks when a grantee-partner or the marketplace simply is not ready.

These are all important learnings and strategies for the Foundation, and perhaps for peer funders as well. What they are not, however, are actual tools for the grantee-partner to use to help them on their path towards sustainability. Over the last couple of years, the Jewish Teen Education and Engagement Funder Collaborative (FC)—a complex, multi-faceted grouping of different funders and organizations from around the country—elevated the goal of sustainability for each of its ten communities in very concrete ways. The FC’s ten community teen initiatives all worked diligently from the beginning to lay the groundwork for sustainability. Community stakeholders were engaged throughout so that our local funding partners, often Federations, designed initiatives that reflected the community’s actual needs and wants—not just what the local partner thought the community needed or wanted. Communities had conversations with program providers at the beginning stages of the grant period about expectations around sustainability. This complex community planning process helped develop teen initiatives that had broad buy-in from the start, thus also enhancing the likelihood of their sustainability.

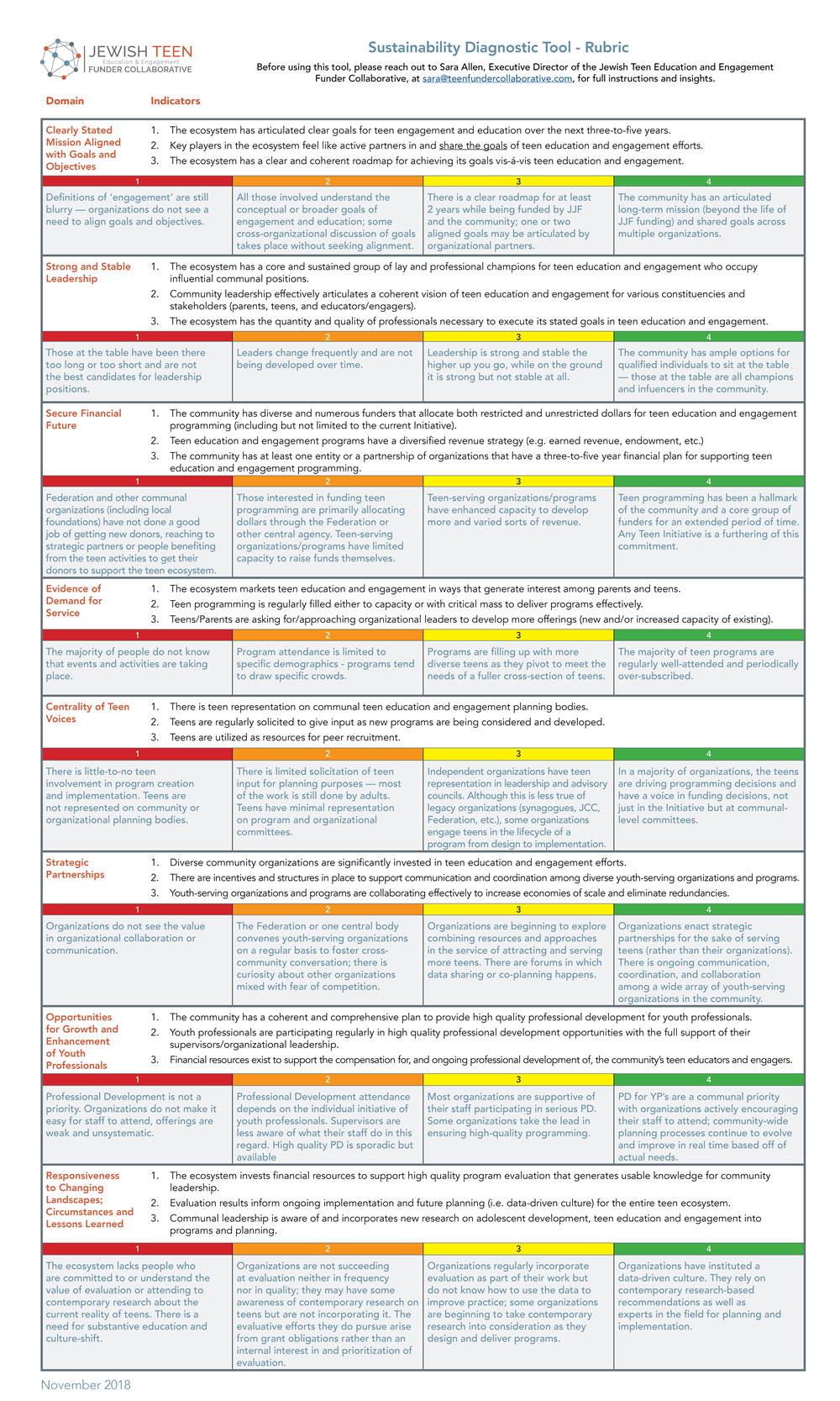

In this vein, the communities came together to develop clear Measures of Success—one of which is to “Build Models for Jewish Teen Education that are Sustainable.” However, defining what success looks like without also offering a way to measure against it would somewhat render it moot. While complex surveys were developed for other measures of success—an appropriate approach in those cases—measuring a community’s readiness for sustainability required something different. That’s when Rosov Consulting, which serves as the cross-community evaluator, developed the Sustainability Diagnostic Tool (SDT) for communities to better understand the ways in which they were developing a sustainable ecosystem. This diagnostic process, which, importantly, communities can use themselves, offers community leadership and stakeholders the opportunity to assess and reflect on their progress towards sustainability.

click here to open image

As seen above, the SDT offers clear indicators and a qualitative sliding scale for communities to gauge progress themselves. Taken together, communities will gain a deep understanding about their readiness to “make it on their own.” Particularly important is that this is a usable diagnostic tool that communities themselves can deploy; each community received instructions to conduct interviews with key community stakeholders. They posed questions to elicit answers that would inform where the teen initiative fell in different categories of the rubric: “To what extent would you say that the leadership of the community’s teen ecosystem has a clearly stated mission for its work?” To what extent would you say that the community’s teen ecosystem has strong and stable leadership?” “To what extent would you say the community’s teen ecosystem has secured a financial future?” With the indicators in mind, to what extent is there evidence in the teen ecosystem of demand for service?”

Like other funders, we have seen expensive efforts we supported grow and build momentum, achieve great programmatic outcomes, but then fail to build the kind of broader communal investment that an initiative needs to endure over the longer-term. The SDT is designed so that grantee-partners can help themselves develop that kind of staying power. We are sharing this now as some communities in the FC move towards the final stages of their grant period. They already planned initiatives, received their first grant, received a renewal, and are fine-tuning the most effective parts of their initiatives. The communities nearing the end of their grant periods are finding great value in the SDT. Equally as exciting is that other communities, in earlier stages of their grant period, are already using the SDT so that the rubric and accompanying interview questions inform their stakeholder conversations and related initiative planning now:

The Sustainability Diagnostic Tool has really helped keep us honest with respect to how we’ve measured inroads and impact in our community’s initiative. Having this rubric has been a great way to remind ourselves what we mean by ‘success’, and has enabled us to validate some paths we’ve taken, or think about course corrections when necessary. – Brian Jaffee, Executive Director of the Jewish Foundation of Cincinnati, the local funder of the Cincinnati Jewish Teen Collective.

The FC itself is a “big” story with many layers, organizations, and learnings. We’re telling one specific, yet critical, part of it now. We hope that by highlighting our Foundation’s learnings regarding sustainability and what we believe to be a critical new tool, other funders and organizations will be able to adapt the new SDT for any initiative that they want to see achieve sustainability. Having sustainability as a principle, as a goal, was important. But the SDT helps us and grantee-partners more definitively and accurately answer that key question: “What would remain if Foundation funding disappeared?”

Before using the SDT, please reach out to Sara Allen, Executive Director of the Jewish Teen Education and Engagement Funder Collaborative, at [email protected] for full instructions and insights.

Aaron Saxe is a Senior Program Officer at the Jim Joseph Foundation.