More than a year into a devastating pandemic and multiple crises, Jewish communities continue to demonstrate resilience, strength, and togetherness that have resulted in powerful moments and experiences of connection, meaning, and purpose. As springtime moves forward and we prepare for the Hebrew month of Iyar, we are grateful to be able to see more light through this pandemic tunnel and to turn a hopeful corner. At the same time, people committed to building community and connection no matter the distance certainly will continue to build on learnings from this challenging period. Emergency, urgency and necessity invited people to discover new (and now tried and true) ways of coming together to learn, meet, grow, debate, sing, dance, pray, serve, eat, and play. Platforms and activities that once may have felt too futuristic, out of reach, or uncomfortable are, for many, now part of our comfort zones and daily lives.

In March 2019, one year before the pandemic, the Jim Joseph Foundation commissioned The Future of Jewish Learning is Here: How Digital Media Are Reshaping Jewish Education. Little did we know that just a year later, many of the insights and findings discussed in that report would become a part of nearly everyone’s life as Jewish education—and engagement, community-building, and so much more—were forced to move online. As we all consider what’s working best virtually, what still needs improvement, and acknowledge the many unknown unknowns still, we want to highlight bright spots of connection and content on virtual platforms that caught our attention over the last year. Below we share a limited* perspective on this from members of the Jim Joseph Foundation team, and call out how the characteristics of online Jewish learning and findings from The Future of Jewish Learning is Here in some ways foreshadowed the world we’re now living in. While the findings from that report speak to many facets of digital engagement today, we connect some specifically to certain platforms and experiences below (although the findings really speak to platforms across the board). The digital engagement we highlight here enable users to engage creatively, with community connection and collaboration at the center of the experience. The future is still bright.

Creative Conferencing Platforms

Key characteristic from The Future of Jewish Learning is Here: Platforms shape the learning experience.

Key finding from The Future of Jewish Learning is Here: Learners use different platforms for different ends.

We’ve seen dozens of platforms shape hundreds of diverse experiences. Two examples highlight how platforms brought users in and engaged them in creative, dynamic ways, based on the key goals and objectives of the gatherings. In some ways, we’ve seen how online platforms make learning and networking even more accessible for people who might not otherwise fully engage in person.

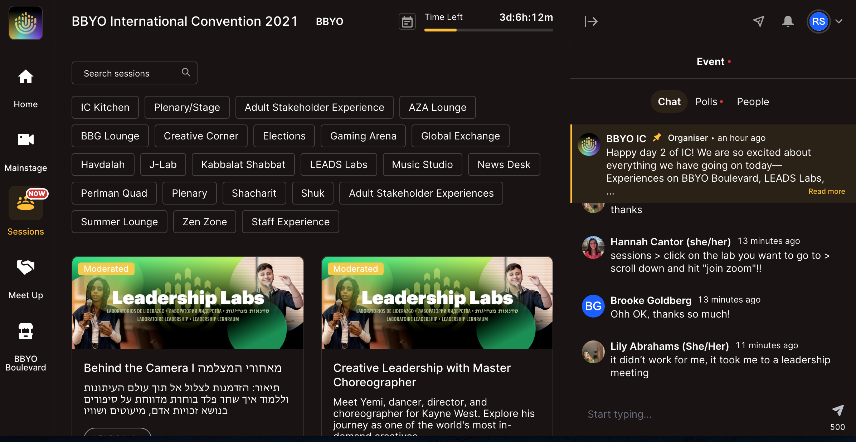

- BBYO’s International Convention (IC) on Hopin: BBYO’s IC is known for attracting thousands of teens from around the world every year. The conference is known for its “nonstop” content so choosing a platform that offered energy, connection and branded physical spaces was key. In February, the experience happened online with Hopin, reaching 2,000+ teens on the platform. Learn more about Hopin.

- Jewish Funders Network (JFN) Conference on Lunchpool: A record-breaking 665 people from 13 countries around the world attended “Strong Bonds,” JFN’s first-ever all-virtual international conference in March, including 129 participants from Israel and 192 first-timers. Networking was a key goal for this conference so before daily sessions and during coffee breaks, participants moved around multiple floors to network around tables by interest area, in pairs and small groups. Learn more about Lunchpool and JFN’s conference concept and design here.

Newish Jewish Podcasts

Key characteristic from the report: Learning is both synchronous and asynchronous.

Key finding from the report: Learners learn in sync with the rhythms of the Jewish calendar.

During the pandemic, we’ve people choosing sometimes to engage in “live” content; other times they consume and engage what they want when they want. While the rhythms of the Jewish calendar still provided an anchor for much content, we saw significant new content and Jewish experiences offered around a range of topics, issues, learnings, and so much more, that was not connected to holidays. Two new podcasts (and one more launching soon) caught our attention for this exact reason.

- Schmaltzy Podcast: A podcast about storytelling, food and everything in between. Learn more and tune into Seasons 1 and 2 here.

- Yeshivat Maharat’s MaharatCast: Building a mikvah, choosing joy, the big questions of end of life, and so much more. Hear from Maharat alumnae on the issues that matter most. The first half of the season is available online here, also on iTunes, Spotify, and SoundCloud.

- Just Leading Podcast: We’re anticipating the May 2021 launch of this 8-episode leadership series. This collaboration features Ilana Kaufman, Executive Director of Jews of Color Initiative, Elana Wein, Executive Director of SRE Network, and Gali Cooks, President & CEO of Leading Edge.

Ready, Set, Play! Gaming Across Generations

Key characteristic from the report: Knowledge, expertise, and power are distributed.

Key finding from the report: Learners access Jewish knowledge beyond Jewish institutions.

Of all the insights discussed in the 2019 report, this characteristic and finding may have been most amplified—and perhaps the evolution of related content most accelerated—as a result of the pandemic. Gaming is just one example of how virtual engagement opens the playing field—everyone can be the teacher and everyone the student. The following examples show how anyone can create content and attract an audience through fun and creative learning experiences.

- Moishe House’s Expedition Nai: This global competition was a four-week battle where participants played with and against friends to win incredible prizes. Players could join teams of 1-5 people any time throughout the expedition and new challenges were released daily. No previous camp experience was required, no entry fee, and no age limit. Learn more here.

- Camp Ramah on Minecraft: When his 14th year at summer at camp was cancelled due to the pandemic, Jake Offenheim created a virtual copy of his actual camp on Minecraft. He downloaded a suite of tools for Minecraft on his computer, fashioned a re-creation of one cabin, then copied and pasted it across camp, changing the shape as necessary. Campers enjoyed an entirely virtual experience thanks to his creativity and technical skills. Read more about Jake Offenheim’s camp re-creation here.

- Jewish Geography Zoom Racing / Who Knows One?: In this game launched in April 2020, contestants are given a name of a Jewish person they have never met, and they race to see who can get that person on the Zoom call the fastest, using only six degrees of (Zoom) separation. The game’s motto? “It’s not who you know, it’s who you know knows.” The seventh episode racked up a respectable 3,000-plus views ran on Facebook Live. Learn more here and follow on Facebook here.

On-Demand/Anytime Content and TV

Key characteristic from the report: Online learning is IRL (in real life), too.

Key finding from the report: Learners integrate online learning and offline practice.

“Recognizing that digital learning environments are not divorced from the physical world reframes the phenomenon from one that happens ‘out there’ in cyberspace to one that is deeply embedded in our everyday lives, both online and offline. The two spheres of learning and action are less distinct than they appear, and both benefit from engagement with the other.” This insight from The Future of Jewish Learning is Here undoubtedly came to fruition out of necessity during the pandemic. People continued to live their lives, pursuing their interests and learning new things—mostly all online. Here are some great experiences and events that engaged people’s interests and identities in meaningful and fun ways.

- Great Big Jewish Food Fest: This well-known Festival took place over 10 days featuring a variety of free events–workshops & conversations, happy hours, and Shabbat dinners, and so much more over Zoom, Instagram, and Facebook. On-Demand access to Festival sessions, Anytime Content and Recipes shared by chefs and presenters were plentiful. Like many online experiences, the Festival was open to all: no experience or talent required. Learn more here.

- Moishe House’s Expedition Maker: A reality show for Jewish artists, creatives, and innovators, this show featured ten “chosen makers” from around the world in weekly challenges where the audience votes to decide who moves to the finale. Learn more and tune in here.

- Bringing Israel Home TV Show: A partnership between the Jewish Food Society and Michael Solomonov, a 5-time James Beard Foundation award-winning chef. In this culinary web series, Solomonov shares Israel’s extraordinarily diverse and vibrant culinary landscape with viewers, via an interactive digital series. Each week, viewers discover the ingredients, spices and flavors that make up Israeli cuisine, alongside the stories of the communities who have brought these dishes to life for generations. Cook along with chef Solomonov and learn more here.

- LUNAR videos: LUNAR aims to highlight the racial and cultural diversity of the Jewish community by celebrating and making visible the experiences of young adults (18-30) who exist at the intersection of Jewish and Asian American in a short-form video series. Check out eight videos, five 5-10 minute themed collective activities and discussion, and three 30-minute long in-depth interviews and learn more about the project here.

Online/Mobile-Friendly Connection and Conversations

Key characteristic from the report: Learning is social.

Key finding from the report: Learners connect with others around Jewish learning.

Over the last year nearly everyone found new ways to connect online for all kinds of reasons, through different experiences, and in various group sizes. These connections not only helped people to maintain Jewish community during the pandemic, but also enabled people to build new community over shared interests and experiences, not beholden to geography. Here are some great opportunities that offer ongoing connection:

- Keshet’s LGBTQ & Ally Teen Shabbaton Retreats: One of a kind Shabbat retreats for LGBTQ and ally Jewish teens, ages 13 – 18, to learn, grow, and celebrate who they are in a warm and vibrant community. Led by teens, for teens, the Shabbaton is a chance to engage in Jewish learning, activism, and self-care. Learn more about other upcoming programs and events on Keshet’s Youth page here and on Facebook here.

- At the Well’s My Moon Message: This text campaign gives subscribers access to monthly spiritual teachings, Jewish wisdom and soulful inspiration sent right to your phone. Texts include reminders of each new moon with teachings from the upcoming Hebrew month, Jewish holidays, 49-day journey of teachings for The Counting of The Omer, and more. Learn more and sign up here.

- Clubhouse: “Clubhouse, a new audio-only social networking app, is quickly becoming the digital version of the Jewish conference circuit hallway. With in-person meetups on hold due to the novel coronavirus and Zoom broadcasts that take on a formal nature, Jewish conference circuit regulars had been searching for a digital duplicate of the informal conversations that are often the main draw of the offline gatherings” (Ryan Torok, from this article). At this time, users must be invited onto the app by an existing user. Sign up here to see if you have friends on Clubhouse who can extend an invite. Follow Clubs that interest you (like Value Culture, who recently hosted a Passover Seder on Clubhouse, Night Of 1,000 Jewish Stars, reaching 43,000 listeners) and People you know and admire to stay up-to-date on meaningful conversations, music, chatter, and more.

Small Group Learning

Key characteristic from the report: Knowledge, expertise, and power are distributed.

Key finding from the report: Learners access Jewish knowledge beyond Jewish institutions.

The examples below come from a variety of Jewish institutions, representing a spectrum of legacy organizations and newer ones. Moreover, the learning experiences below show how distributed learning can be in the digital realm–nearly anyone can be a teacher when matched with the right student. Not only is knowledge a mere click away, but the person transmitting that knowledge can embody a diverse and varied background and skillset. These digital offerings demonstrate more expansive and contextual thinking on the meaning of traditional terms like “teacher” and “student” today.

- Hadar’s Project Zug: An online havruta (one-on-one) learning program that provides participants with weekly learning for various lengths of time from five to eleven weeks long. Holiday-centered courses occur seasonally. Zug can help match you with a havruta or you can come ready with a learning partner. Each Zug/pair will schedule their online video conversation at a time convenient to their schedules. Check out this intro video on how it works and learn more here.

- Hillel’s WinterFest: Hillel’s first-ever virtual winter festival was designed to bring light into students’ lives during the darkness of winter through small group learning, cool prizes and swag, and of course, Jewish wisdom. Nearly 1,500 students from 263 campuses in 9 countries around the world connected deeply with each other and Jewish wisdom. Read more about the winter festival here.

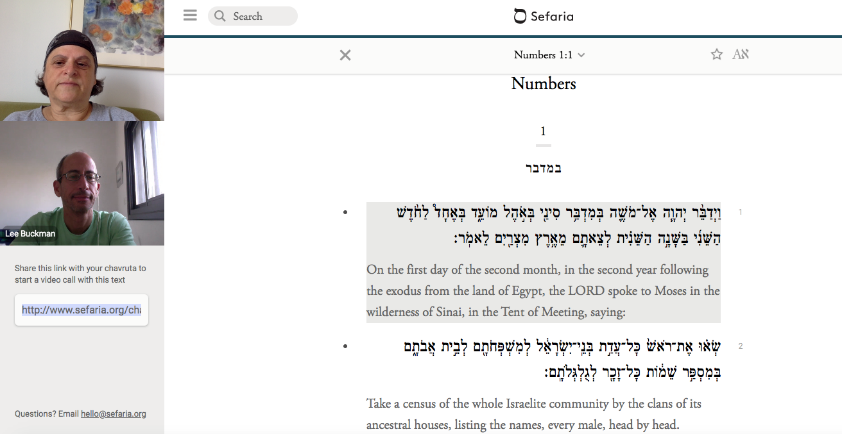

- Sefaria’s new Chavruta Feature: Sefaria’s newest feature, Chavruta, allows users to connect with another Sefaria user to study a text face-to-face on the Sefaria platform. Check out the tutorial and learn more here.

- JIMENA’s Buddy System: This creative project by JIMENA (Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa) pairs older adults and people of all ages with buddies to encourage ongoing and regular connection for weekly check-ins via Facetime, Zoom, or just the good old phone. As so many of us are alone with limited opportunities for social interaction, this matching program encourages new connections and relationship building. Learn more here and sign up to be a JIMENA Buddy via this quick survey.

- JDC Entwine’s Insider Connections: Global Virtual Service: Entwine, known for its impactful global travel and volunteer experiences, designed virtual programs that will evolve into a fully blended platform in the future. One program enables young adults to volunteer for an hour per week over three months with isolated JDC-supported elderly, teens, and children overseas. Participants receive pre-service training, regular check-ins and support as a cohort, and have flexibility in how and when they connect with their overseas “client” for company, conversation and/or practicing English. Learn more about volunteering here.

*Hundreds of individuals, teams, organizations, and collaboratives have worked tirelessly to keep their communities connected over the last year, despite enormous odds and innumerable challenges. This small list is a representation of some of what we’ve seen and by no means includes all of the incredible examples of creative projects, gatherings, and experiences that have made a daily impact on all of our lives. Please comment below with other examples to highlight and celebrate their impact!