For many students, taking a second language used to mean choosing between French and Spanish, and even then not until high school. These days, however, more students have been signing up for Hebrew in public and charter schools—and at much younger ages.

More than 6,600 students were learning Hebrew in a public-school or charter-school setting in 2018, according to a report issued by CASJE, the Consortium for Applied Studies in Jewish Education, and George Washington University’s Graduate School of Education and Human Development.

The report, “Mapping Hebrew Education in Public Schools: A Resource for Hebrew Educators,” further noted that 35 schools were offering Hebrew-language classes. Of that number, 17 schools serve students in either elementary or middle school, while 18 serve grades nine through 12. And, according to the survey, 19 of the schools reported increased enrollment in Hebrew classes with only 1 school reporting a decline in the last five to 10 years.

“We really had no idea what we would find; we just had a sense that there were schools out there,” said Sharon Avni, who co-wrote the report with Avital Karpman. “I think the biggest surprise is that there are 2,000 students in traditional public schools studying Hebrew language.”

“It’s sort of a startup experiment, it’s so diverse,” added Karpman. “You do have some charter-school networks,” like Ben Gamla Charter Schools in Southeast Florida and the Hebrew Public Charter Schools for Global Citizens, but, otherwise, “every individual community we spoke to had different reasons and different communities of students. There isn’t a thread running through all these Hebrew programs.”

There are the Hebrew charter schools in cities like New York and Washington, where parents aren’t necessarily looking for Hebrew-language education, but are drawn to the perceived higher quality of education offered than in inner-city public schools. The student populations of these schools are often different than those run by the Ben Gamla Charter School Foundation in Florida or the Hatikvah International Academy Charter School in East Brunswick, N.J., both in areas with a significant Jewish populations.

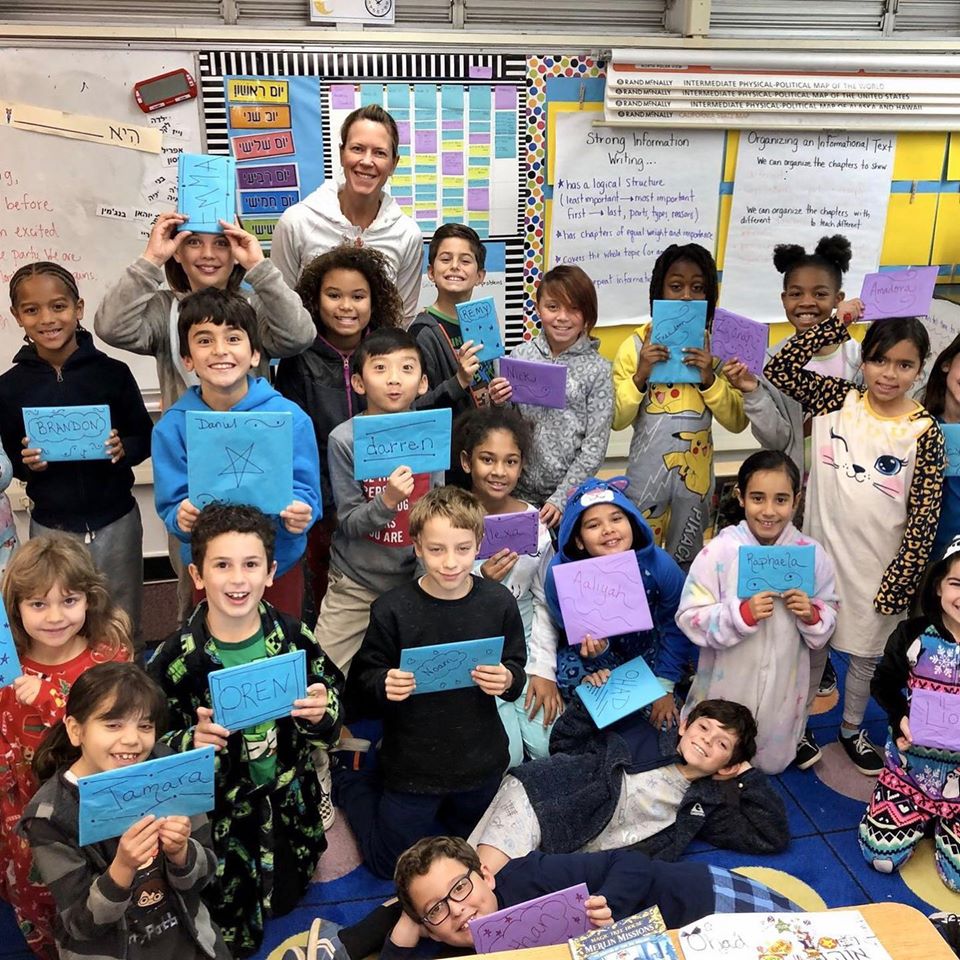

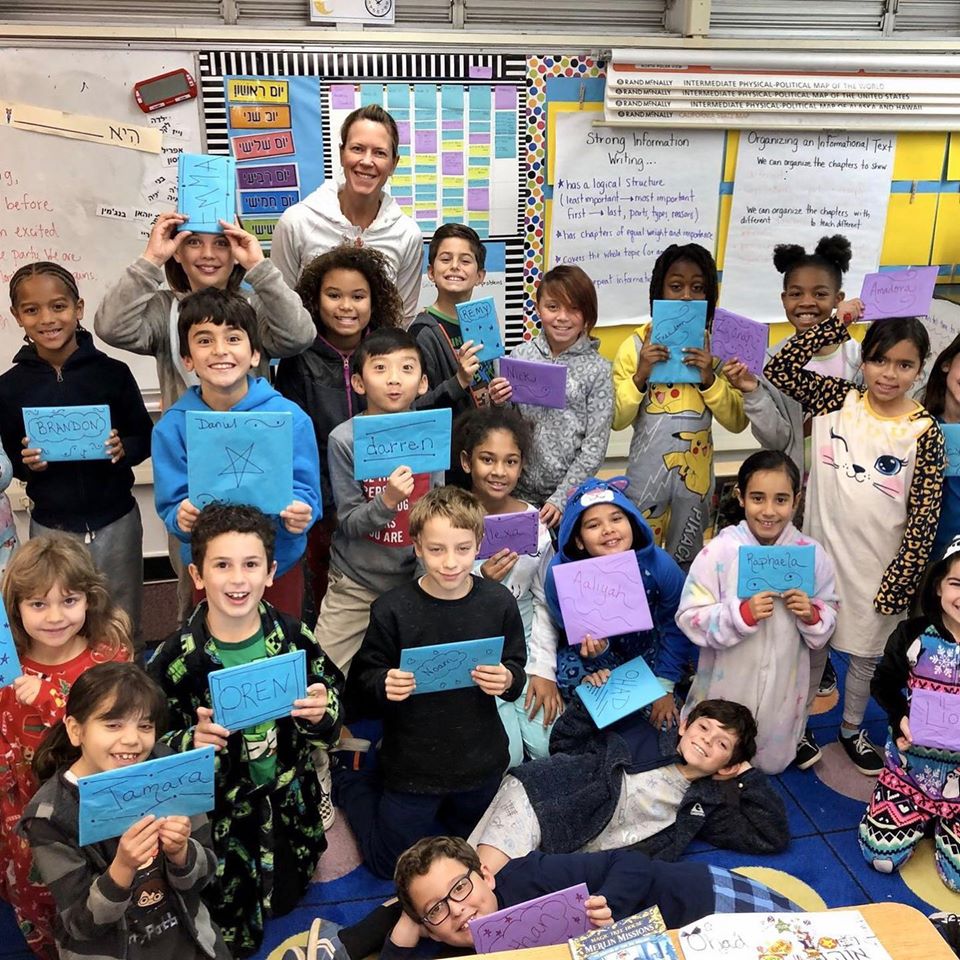

Children at the Kavod Charter School in San Diego, which started seven years ago with just 55 students, has since grown to 350 students. Most of the day’s classes are taught in Hebrew. Source: Kavod Charter School via Facebook.

The enrollment increase in Hebrew classes is being felt at the Kavod Charter School in San Diego, which started seven years ago with just 55 students and has grown to 350 students. This year the school added two sixth-grade classes. Some students are from Israeli families now working and living in Southern California, and others are there because they want their child to learn a second language.

“It’s a public school with the mentality of a private school,” said Ronit Ron-Yerushalmi, language and global-studies director at Kavod. “Our classes are smaller, and we have more resources.”

While math, reading and writing are taught in English, much of the rest of the school day—from morning meeting to art class to physical education and even recess are conducted in Hebrew.

‘It creates opportunities in the future’

Ron-Yerushalmi spoke with JNS during the seventh annual “Hebrew in North America Conference,” which was held in mid-November in Newark, N.J., and sponsored by the World Zionist Organization’s Department of Education and the Council for Hebrew Language and Culture in North America. As many as 400 people attended the two-day conference.

Ronit Ron-Yerushalmi, language and global-studies director at Kavod. Credit: Courtesy.

While the interest in Hebrew-language classes and charter schools definitely benefit Jewish communal interests, plenty of academic research suggests that learning a second language is beneficial to children’s cognitive growth, results in higher testing skills and makes them more empathetic to others, as language and related concepts allow them to see people from a different perspective.

“I think this is one of the main marketing points that Hebrew charter schools make to non-Jewish families—that it’s good for your children to learn another language, that it’s good for the brain development, and it creates opportunities in the future,” suggested Rabbi Andrew Ergas, chair of the Council for Hebrew Language and Culture in North America.

For Jewish families, he continued, having Hebrew in public schools meets the students where they are. It gives them a connection to their heritage and, oftentimes, other Jewish students while aligning with their educational needs.

“It’s not religious, not political,” said Ergas. “Instead of Spanish, you are taking Hebrew.”

The academic and cognitive benefits of Hebrew, as with other languages, is why the focus is shifting to growing a population of Hebrew-language educators who cannot merely speak the language, as has been the case before, but who are experts in teaching a second language and ensuring that students met recognized standards of understanding as they would if they were taking Spanish.

Rabbi Andrew Ergas, chair of the Council for Hebrew Language and Culture in North America. Credit: The Council for Hebrew Language and Culture.

“We are in a moment in American society,” said Avni. “People think we are less inclusive, but multilingual and bilingual are seen as a great thing … and families are interested in having their children learn more languages.”

Finding teachers ‘is the hardest challenge’

Despite the increase in interest, the total number of schools and students with Hebrew education remains relatively small compared to the number of Jewish students in the public-school sphere. Experts believe that could change if one deficiency was rectified: the lack of qualified, accredited Hebrew-language teachers.

For years, say those in the field, Jewish schools relied on people who were simply fluent Hebrew speakers to teach Hebrew-language lessons, regardless of whether or not they were experienced teachers; understood educational pedagogy surrounding teaching as a second language; or even knew about classroom management and assessments. Such ad hoc education would not be welcome in most public-school systems.

“I get calls all the time from schools in all different areas of the country that say, ‘We can’t continue our Hebrew program’ or ‘Our students want a [Hebrew] program,’ ” reported Karpman, noting that it’s difficult to staff these programs, especially if they are in smaller communities. “There’s a need out there, but we don’t have people going there.”

She noted that in some cases, teachers who could be retiring are staying because there is no one qualified to take over. In other cases, such as in Closter, N.J., where there is a strong Israeli ex-patriate community, families asked for a Hebrew-language class in the public schools, but the district reportedly couldn’t find a certified teacher to staff it.

Finding teachers is “the hardest and biggest challenge,” declared Ron-Yerushalmi, who noted that even experienced teachers from Israel may not succeed as Hebrew teachers in U.S. public or charter schools. “What is expected as teachers in Israel is very different than what is expected here.”

Those expectations include communication with parents and writing lesson plans, along with cultural differences and a language barrier.

To ensure that teachers of Hebrew language have the proper tools to be effective educators, the School of Hebrew at Middlebury College in Vermont offers a master’s degree in teaching Hebrew as a second language.

“We want to professionalize the skills of teachers, and a way to do it is for them to learn more about second-language acquisition,” said Vardit Ringvald, director of the School of Hebrew at Middlebury. “Teaching language is a discipline, and we need to professionalize that discipline. … I had adults in their 40s and 50s who have come to my classes and were crying because they saw that they weren’t doing things right—and they are frustrated.”

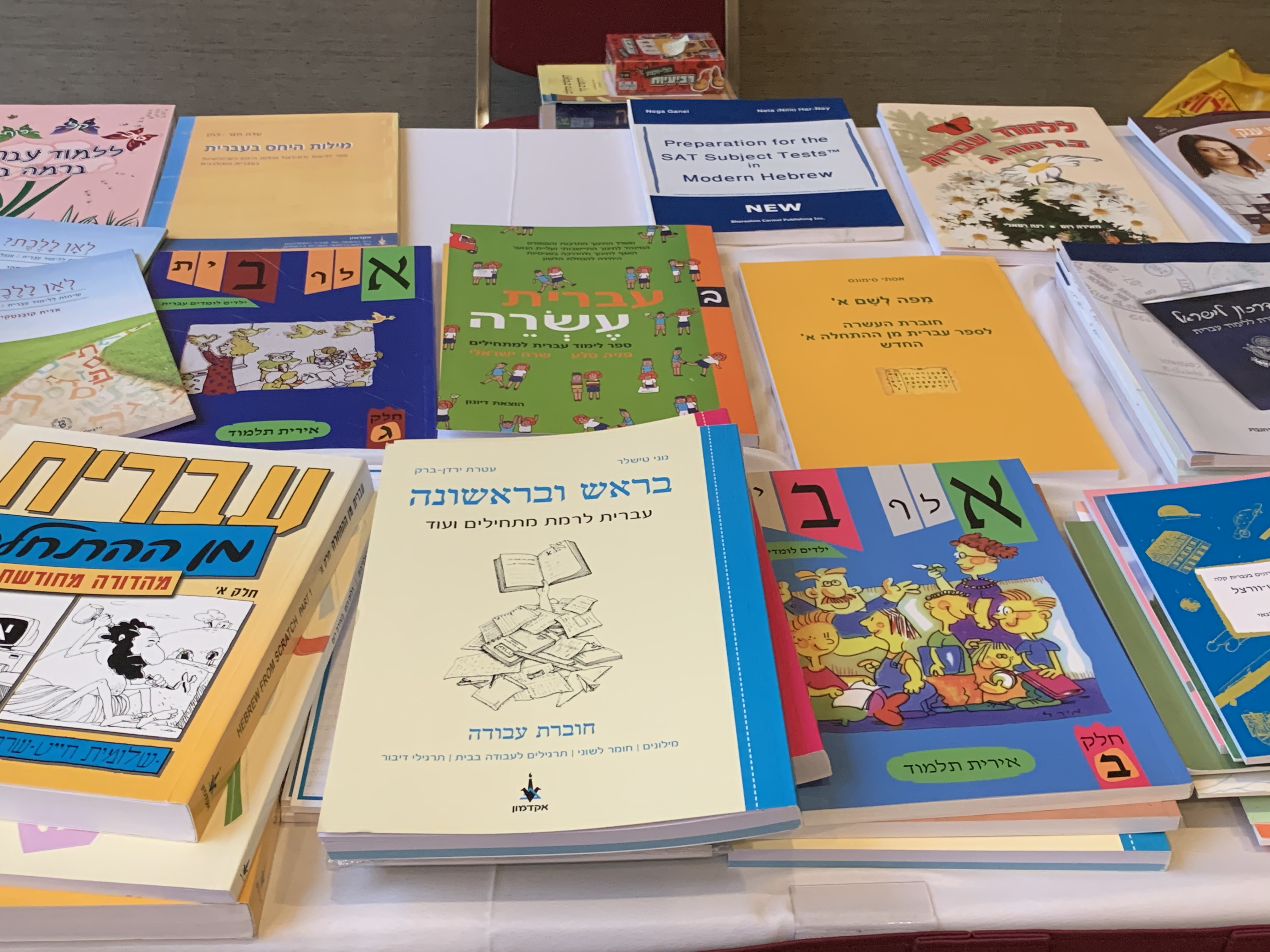

To recruit new students to the teachers’ program, she and her colleagues set up an information table at the Hebrew conference in Newark in November; more than two-dozen people applied for the program on the spot.

‘It’s a language people are using’

Veteran Hebrew teacher Binnie Swislow knows there are great educators out there who are passionate about the language, but that it’s important they also have the pedagogical tools to meet the needs of today’s schools and students.

“I’m not fighting the battle of ‘Can you be an excellent teacher?’ That’s not what this is about,” said Swislow, who taught in Chicago-area public schools and is a founding member of the Council for Hebrew Language and co-founder of the National Association of Hebrew Teachers. “This is about a system. It is about following the same methods that all the other languages that are being taught.”

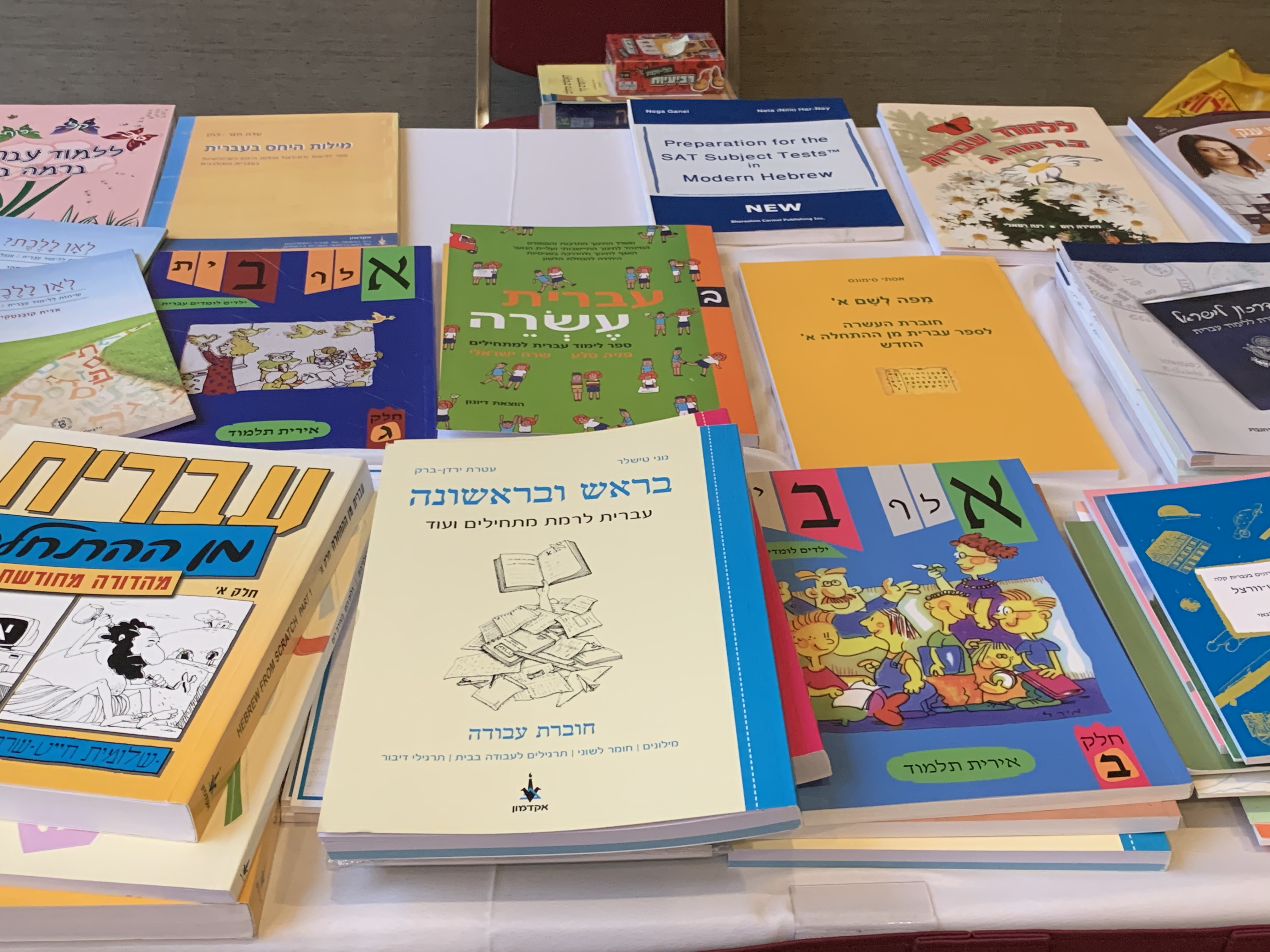

A collection of some of the materials available for educators at the Hebrew conference in Newark. N.J.

Swislow is a consultant at The iCenter for Israel Education in Northbrook, Ill., which bills itself as the North American hub for Israel education. It’s located at what may be considered the epicenter of Hebrew education in the public-school sphere, as more than 600 students in Chicago-area schools are enrolled in Hebrew classes.

One of those previous students is Dan Tatar, director of communications and outreach at iCenter. He knows firsthand how impactful Hebrew-language classes can be, especially with the right teacher.

Yes, Tatar learned how to conjugate words in Hebrew, but that wasn’t what brought the language to life for him. Rather, it was how their teacher connected them to Israel, he said, “through news stories and video or events.”

“It became real,” he said. “It’s a language people are using, and it connected me to something deeper. We see that with students today.”

For educators of Hebrew in the public sphere, communal concerns about the role of religion seem to come up more frequently than in other languages, though experts say teachers know not endorse Judaism.

Charter schools, reported Avni, “have demonstrated that it is possible to have Hebrew in public schools. They are the proof of concept. They’ve shown you can do it and not run afoul of constitutional issues, and that there’s a demand for it.”

She went on to say that “language is never devoid from culture.” In a Spanish class, students might learn about Catholic holidays because most Spanish countries are primarily Catholic. “It is a spoken language, and in schools is part of world-culture curriculums. Hebrew is a bit more complicated because there’s only one place with native Hebrew speakers,” and that is Israel.

“But what we saw in our observations and what teachers tell us is that they teach Hebrew, and also about Israel and Jewish culture, but not in a way that’s promoting or proselytizing,” she continued. “They find a space to teach about the language and the people who speak that language without crossing the line of separation between church and state.”

Source: “Hebrew becomes hip in American schools as a boon for kids and communities,” Faygie Holt, Jewish News Syndicate, February 4, 2020